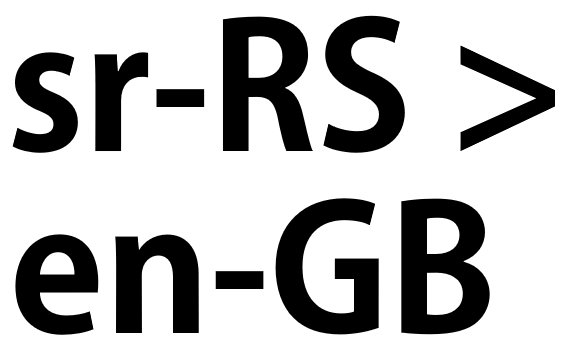

Choose Odista for Serbian-English translation:

- based in Serbia

- native English speakers only

- dedicated Serbian-English translation service

Odista is a unique agency, focused solely on translation into English from Serbian and the other related former Yugoslav languages. We are based in Serbia so are in contact with the living language. And ALL of our translations into English are carried out by highly educated native English speakers, fluent in Serbian.

News

- Indigo Lost – a novel – our latest book translation from Serbian

December 2, 2020 2:39 pmWe have been working for over a year on the translation of a Serbian novel by Aleksandar Gutović titled Indigo Lost, and it’s finally out! See the first part of this article about our book translation portfolio to find out more about Indigo Lost (it’s a great read – we think Aleksandar will go far!) and what translating a work of fiction entails.

- “Employer branding” – a new video from Adižes SEE

November 27, 2020 9:42 amASEE, the top South-East European management consultancy, part of the Adizes Institute network, have just put out a new, short video about employer branding. “You have organisations that look very nice from the outside but their employees go to work with gritted teeth every morning”, says Zvezdan Horvat, professional director. “Companies must be willing to pay the price of having values, and not just ‘talk the talk’.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-l1M6FBVVA The subtitles were translated by Odista from Serbian and then adapted by the client, though we can do that part too. Odista has worked for many years with Adižes, translating their various management and business consultancy materials and even translating part of the autobiography of Ichak Adizes, which is due to be published soon.

- Interview with Mark Daniels

October 1, 2020 11:22 amOdista’s Mark Daniels recently gave an interview to Čedomir Pušica, a translator well known in Serbian translation circles for his book Priručnik za prevodioce (“The Translators’ Manual” – not currently available in English). If you want to find out how a supposed Englishman ended up in Serbia running an agency solely devoted to translations from Serbian into native English, then check out the interview. It’s only available in Serbian unfortunately, perhaps we will get it translated into English at some point (look, you think we have time to translate stuff for our own websites as well!?) but for now Google Translate will help you get the gist, and maybe give you some extra laughs along the way! https://translate.google.com/translate?sl=sr&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lingvista.rs%2F2020%2F09%2Fmark-daniels.html

Serbian translation trivia

- “Dizajniran”

This is probably another losing battle, but due no doubt to lazy translation from English into Serbian the English borrowing dizajniran is increasingly being used in Serbian where it is quite unnecessary. The word dizajn (“design”), since it made its way into Serbian, probably some decades ago, has always primarily referred to visual or graphical design. The emphasis is on the visual/aesthetic type of design. In recent years however, the English word “design/designed” is increasingly being used in Serbian to mean the manufacture of a product, process or anything else along those lines, not just in the visual sense but in terms of all its characteristics taken as a whole. This usage is especially prevalent in advertising (an industry which is notoriously sloppy when it comes to translating advertising slogans wholesale, as we have lamented many times before). For example, “pogledajte kako izgleda rover koji je dizajniran da se vozi po Marsu” (“check out the new rover which has been designed to be driven on Mars”). Here, dizajniran is really an alien (pun not intended) usage of this word in Serbian. It sounds as though it is referring to the visual design of the rover, but of course it’s not, it’s talking about everything – the mechanics, the electronics etc. etc. We don’t recommend this usage of dizajniran and would never use it like that in any of our English-Serbian translations. A better alternative in this case might be projektovan, which is used very often when talking about industrial, engineering and those kinds of design. Other words you could use for “designed” in Serbian might be osmišljen (something like “devised, thought out”), koncipiran (“conceived of” or “intended for use [in such-and-such a way]”) or maybe simply napravljen, proizveden [tako da] (“made, produced/manufactured [in such a way as to…]”. Yes, we realise projektovan is not a Serbian word in origin, and nor is koncipiran, and we recognise that these processes of assimilating foreign words are probably inevitable. But a hallmark of good-quality writing is aiming to NOT jump on the bandwagon with new words before they are well and truly adopted, and always favouring older more established words. This takes more effort than lazily borrowing the word from the foreign language. This is another way we ensure a high standard of production in Serbian (or English) in our translation work.

- Translating bureaucratic language from Serbian

Like a lot of former “Communist bloc” countries, Serbia is rather prone to excessively bureaucratic or flowery turns of phrase where they aren’t necessary (are they ever necessary?). In English it’s become something of a joke – for example people have long enjoyed playing with job titles. Can you guess any of these? Environmental maintenance officerMedia publications administratorRefreshments and nutritions supervisorRevenue protection officer They are, in order: a street cleaner, a paperboy, a canteen cook and a ticket collector. But this kind of unnecessarily inflated description is done in Serbia all the time. Just the other day we translated a report from an NGO that described someone’s occupation as: vrši uslugu uređivanja zelenih površina –“conducting services in maintaining green surfaces”. But is it really necessary to describe someone’s job in such ornate terms? Without wishing to denigrate anyone’s occupation (the project the NGO is involved in is a really good one, promoting self-employment as a way out of poverty for vulnerable groups such as Roma people), green surfaces are gardens and lawns – the guy basically mows lawns, digs gardens and pulls weeds. We are pretty sure the word for that in English is “gardener”, and that’s how we translated it. Sometimes you just have to cut through the bureaucratese when you are translating because to try to translate a phrase like that in a literal way means to add a layer of obfuscation that effectively doesn’t “translate” the phrase at all. It’s not just job descriptions, Serbian is in love with a great many phrases that we have difficulty translating into English but seem to be firmly entrenched and we can’t just skip over them. Here are a few more which perhaps we will look at individually in future articles: rešiti stambeno pitanje – lit. ‘to resolve your housing issues’. The phrase is a standard one meaning to secure/arrange permanent (and legal/long-term, appropriate) accommodation or housing for yourself/someone. It’s actually very commonly used and might informally be translated “get a roof over your head”. For example rešiti stambeno pitanje for refugees would mean finding them a permanent or long-term solution in regard to housing, especially if they were living long-term in unsuitable or legally problematic housing. But people say it informally too – “I bought an apartment, I’ve finally ‘resolved my housing issues'”. Very tricky in English and there is no single way to translate it, and so common in Serbian, despite its bureaucratic origins, that it won’t be going anywhere any time soon.ostvariti svoja prava – lit. “to realise/exercise/pursue your rights”. Not unusual-sounding in English, but very vague, what does that specifically mean? It could be used in many contexts in Serbian but usually it relates to “getting something done” and securing some statutory right, say, securing an invalidity pension or some other benefits from the government. You’d think that wouldn’t require a special phrase, you just go and do it, right? But remember, in a bureaucratic society, securing even your basic rights can very often require a lot of red tape and even greasing the right wheels. In English we might prefer to simply state what specific “right” it was you “exercised” – “I got my pension sorted out today”! By the way, we have a separate article about this specific phrase – ostvari(va)ti prava, which has some additional thoughts on this.vršiti nezakonite radnje – lit. ‘to conduct unlawful acts’. It just means to commit a crime, but the media, police and criminal justice systems for some reason like to make it sound more impressive than it was! There are many, many such examples, and the point we really want to make here is about translation. When translating from Serbian to English the translator needs to make a decision – is there anything to be gained from attempting to translate such phrases “literally”. Indeed, can it even be considered a “translation” if the reader of the target text is none the wiser as to the meaning? Of course, there are many examples of bureaucratese in English too, and the modern science of management has been a particularly rich source of such phraseology, but the UK seems to have never had quite the affinity for it that the former Communist countries have. The Plain English Campaign has likely played an important role too. But at Odista, as translators working primarily from Serbian to English, we are in the business of conveying meaning, and we are committed to communicating not to word-for-word literal sense – which very often makes no sense at all – but the plain, understandable language which strives to communicate the intention behind the source text so that your reader is left in no doubt as to what you meant to say.

- Domaći is not domestic

Another Serbian word that gives translators endless problems is domaći. The word is from dom – “home” – and is an adjective that, loosely speaking, describes things relating to the home (e.g. every kid’s favourite, domaći zadatak – homework). However it also has the meaning of “not foreign”, “local”, and this is where translators frequently fall down (usually, though not always, those non-native English speakers translating from Serbian). Yes, domaći COULD sometimes be translated as “domestic”: bruto domaći proizvod (BDP) – gross domestic product (GDP)domaći let – domestic flight (i.e. one within the same country)domaća politika (not such a common expression) – domestic policydomaće životinje – domestic animalsdomaći terorizam – domestic terrorism However we unfortunately very often see usages of domaći which cannot be translated “domestic” and where another solution should have been found in English: najveća domaća konferencija u oblasti informacionih tehnologija – “the largest locally-held/Serbian/national conference…”, NOT “domestic”. The only time you will find the phrase “domestic conference” if you Google for it is on non-English websites!domaća hrana – this one comes up all the time, and the expression in Serbian means “traditional/national/ethnic/home-made food”, something along those lines, and should NEVER be translated “domestic food”. Don’t even think about it!domaća serija – Similar to the example above with konferencija, this refers to a television series that was produced in Serbia, and “domestic” would not be the suitable word here. A suitable translation would be “locally-produced”, “Serbian-made” or, more idiomatically, “homegrown” (our preferred solution, provided it’s not overused).domaći izdajnik – an expression that became heavily used in the post-Second World War period (and in post-Communist dictatorships all over Eastern Europe) to mean someone who had collaborated with “the enemy”. Well… “domestic traitor” does come up sometimes, but it’s really far more common to say “collaborator” (e.g. “Nazi collaborator”). It also works the other way – “domestic violence” should never have been translated into Serbian as domaće nasilje. For one thing, domaće when referring to the “home” has a positive connotation, as somewhere warm and pleasant, unfortunately not an appropriate sense here at all. The proper (and legal) term in Serbian is porodično nasilje (“family violence”), although unfortunately the phrase domaće nasilje has made inroads under the influence of English in recent years. So you can see that although there is some overlap in the meaning of domaći and “domestic”, there is by no means a direct correspondence and at the least one should look more carefully at whether it is appropriate in English or whether a more idiomatic English expression ought to be used.